fall 2025 issue

The artist explains why the African American funk aesthetic is integral to her practice and her forthcoming project, a reimagining of the Seattle World’s Fair in 1962.

September 15, 2025

Xenobia Bailey creates artwork that celebrates the African American funk aesthetic because, as she says in this interview with scholar and curator Terence Washington, “that’s the aesthetic I know.” While many contemporary Black artists draw parallels between their practices and jazz, Bailey argues that funk is a more authentic and accessible expression in African American culture because of its more medicinal and earthy qualities. The African American funk aesthetic grounds Bailey’s practice as a designer and fiber artist. In this excerpt from their oral history interview, Bailey and Washington unpack the motivations behind her forthcoming project, a reimagining of the Seattle World’s Fair in 1962 that continues her epic work Paradise Under Reconstruction in the Aesthetic of Funk. In this iteration, Bailey utilizes her archival research to recreate a nonfictional, mystic timeline of the cosmic evolution of African Americans’ progress in science and technology from the seventeenth to twenty-first centuries. Through their discussion, Bailey highlights her desires to continue to learn about underexplored aspects of Black history and create art that helps to remedy oppressions faced by the communities she belongs to.

—Janée A. Moses, Director of the Oral History Project

The Oral History Project is made possible with a major grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Additional support is provided by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council.

Terence Washington Before we go deep into your formal training at the University of Washington and earning your bachelor of industrial design from Pratt Institute, would you tell me about the World’s Fair in Seattle?

Xenobia Bailey The Seattle World’s Fair in 1962, also known as the Century 21 Exposition, was themed around technology, optimism, science, and the future of commerce and industry. During that time, my brother, my younger sister, and I were being bussed across town to go to what had been an all-white school. We would travel directly in front of the area where the fair was going to be held. We saw the fair’s construction and, later, its disassembly. We saw the development of the entire fairgrounds, including the Space Needle, which was the central attraction of the fair and is now a designated Seattle landmark, and the monorail that transported everyone to the fair from downtown Seattle.

This fair was supposed to represent the future development of the world and a projection of the twenty-first century, with a monorail for local transportation and towers that reached into space. The fair included a section called Boulevards of the World, with pavilions representing many major countries, but there was no direct representation of African countries. Instead, Africa was represented by an African boutique that was owned by an African American couple who lived in the Central District, the major Black community in Seattle. This couple used to go to different countries in Africa and return to Seattle with baskets, fabric, and wood carvings. The organizers of the fair included their shop in Boulevards of the World, and visitors bought imported African goods made for tourists. That’s how they represented the continent of Africa in the twenty-first century. On the other hand, America had all these robots and the Space Needle and the monorail.

I’ve recently returned to the World’s Fair site because I’m doing research for my next body of work, a fictional version of a deferred African American Pavillion of the present. I’m studying the progression of African Americans in 2025 and where we would have been if we had developed in the way that W. E. B. Du Bois proposed at the 1900 Paris Exposition, where he organized an exhibit on the progressive state of African Americans. I’m creating a timeline for a fictionalized world’s fair pavilion of the African American experience, highlighting descendants of the transatlantic slave trade, specifically the radical, free, elite Black community of the eighteenth century in Philadelphia. I want to explore how they would have evolved. What I have researched so far about their engineering and sciences shows how they were already mentally decolonized. They had Edwardian and Victorian material cultural aesthetics that they blended with their African American experience in industrialized North America.

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania has an amazing archive. I’ve been able to go through journals, handwritten letters, and other printed material because this elite Black community owned a printing press. This community was one of the main stops on the Underground Railroad. I had always believed the Underground Railroad was a group of radical white benefactors. I did not know there was a radical free Black community during that period. Not only were the members free, but their parents were born free, having never been enslaved in the United States. They organized local community fairs and national conventions on the East Coast. These were their own organized expositions, showcasing their most recent progress. Black people who were able to travel across the country during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century took advantage of the opportunity to share information and be inspired by the different scientists, engineers, landowners, and businessmen. By exhibiting progress through these fairs, they evolved with their material culture and lifestyle. In my Black studies courses in college in the 1970s, I had the opportunity to do research in a few early American archives of African Americans’ progress and study the significance of Africa’s natural resources, but I only saw African Americans in chains or running in rags trying to find freedom. But this community in Philadelphia was free. Free.

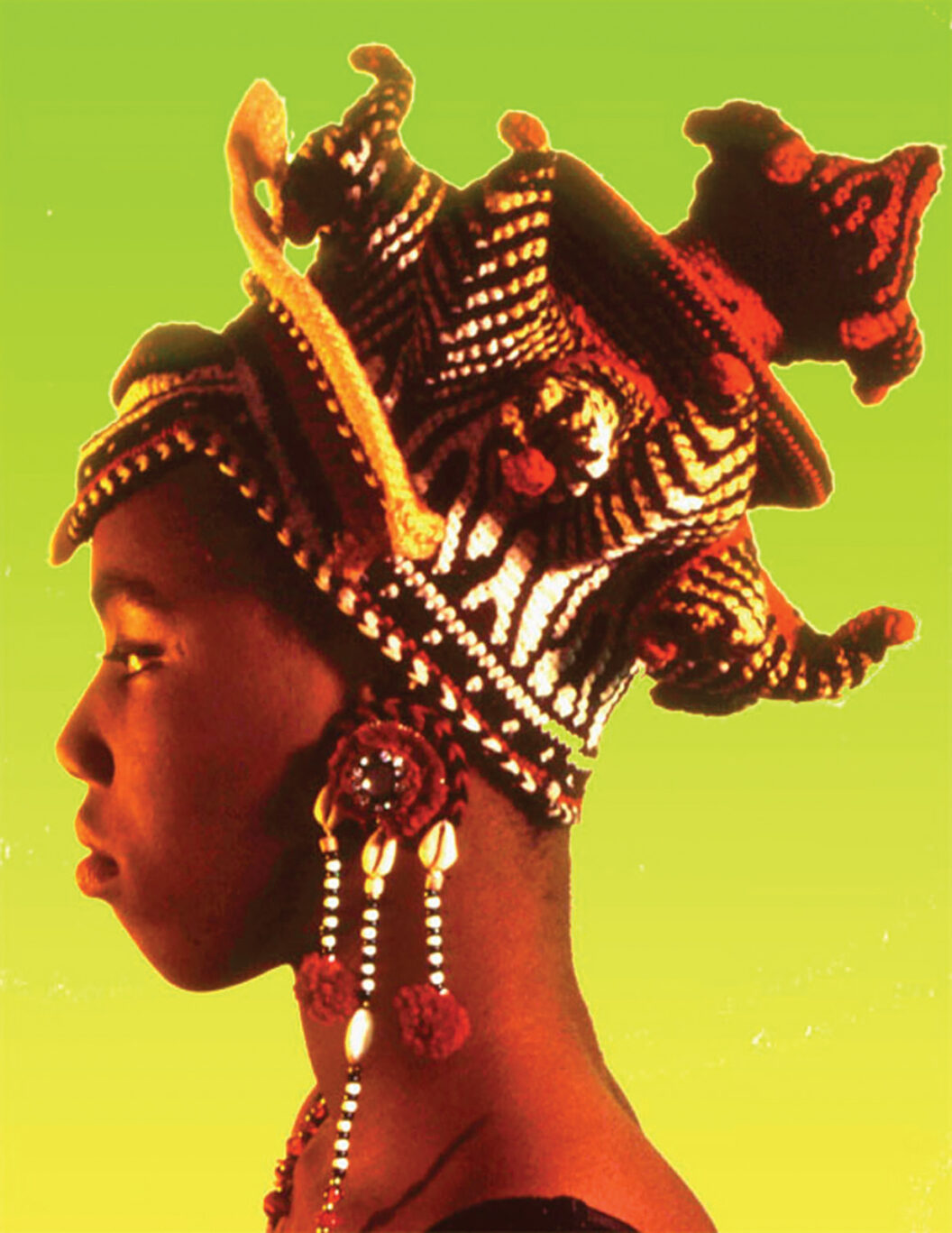

Xenobia Bailey, Sistah Paradise Crochet Crown, 1990, single-stitched, hard-crochet headwear with four-ply cotton and acrylic yarn. Photo by Xenobia Bailey. Courtesy of the artist.

TW Your description of this body of work is interesting. It sounds like an Afrofuturist retrospective. You’re looking back at the Seattle World’s Fair of 1962 and seeing what the organizers missed, what they ignored. It’s also a meditation on the different definitions of freedom that Black people had, none of which were taught in Seattle schools.

XB I did not learn this history in any school. I learned about this after doing research supported by the fellowship I received in 2022 from the Center for Craft in Asheville, North Carolina. I did my research in Philadelphia and took advantage of the many free public libraries and private archives. For example, I learned the Harlem Renaissance didn’t originate in Harlem; it started in Philadelphia with Alain LeRoy Locke, a philosopher, scholar, historian, and writer. He earned a PhD from Harvard University and was the first Black Rhodes scholar to attend the University of Oxford. He was a free thinker and a Black progressive and traveled all over the world teaching, studying antiquities, and meeting with African scholars.

I also didn’t know that free-thinking African scholars met with African American scholars during that period. In fact, the Harlem Renaissance was originally conceived as the New Negro Movement for social, political, and economic equality. It was supposed to be another attempt at Reconstruction, a continuation of what W. E. B. Du Bois displayed in the American Pavilion in Paris in 1900. Instead, the white benefactors who funded the movement and its artists, writers, musicians, and scholars, like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, wanted them to narrowly create the kind of works that they wanted to collect, what they called “Negro art.” They did not want progressive Black art. They wanted the artists to create from a primitive aesthetic. That’s why illustrations and photographs of the performer Josephine Baker have an abstracted, primitive aesthetic to them. There have always been challenges to progressive intellectual concepts.

Xenobia Bailey, Paradise Under Reconstruction in the Aesthetic of Funk, 2016, digital photo collage on vinyl. Photo by Xenobia Bailey. Courtesy of the artist.

TW I wonder if the dynamics you’re describing about being free as a Black artist in relation to the social constraints of being a Black artist became more obvious to you after you enrolled in school. Could you talk about your decision to go to Pratt Institute? How did you get there, and what was your experience?

XB I learned about Pratt from Charles “Buddy” Butler, who was the director of Black Arts West, a community theater group in Seattle’s Black community in the 1970s. I was interning there as a costume designer when Buddy noticed that I’d created a bunch of drawings with a big collection of pastels my mother gifted me. He gave me my first solo exhibit, which was in the theater’s corridor art gallery. I showed all my pastel drawings. After the exhibit, Buddy told me he graduated from Howard University and worked in New York City’s theater community. He told me about Pratt and all the amazingly talented students who went there. He showed me some of their artwork, and I said I’d love to go to a school like that. So, I applied with my pastel drawings and was accepted. The admissions committee wanted us to draw a portrait of ourselves and draw a monument. I drew a monument of Judith Jamison, the dancer and choreographer with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, as a fountain with water splashing for her swirls. Black Arts West gave me a $1,000 scholarship and the Seattle chapter of The Links, Incorporated gave me a $1,000 scholarship. Pratt’s tuition was about $40 a credit.

TW So, right after high school you were doing costume design, dancing, and exhibiting at Black Arts West?

XB Yeah. And at that same time, I was enrolled as part of the affirmative action program at the University of Washington. That was the only way I could have gotten in to college. In high school, I was mostly given D’s, even after I did work for extra credit. But in college, the professors interacted with me in a way I had never before experienced from a teacher. I was getting good grades. When I transferred to Pratt from the University of Washington, I was on the dean’s list. I didn’t even know what that was. I thought I was in trouble when they told me I’d made the dean’s list.

It felt like I finally had a breakthrough when I got to college. I had better communication with the instructors there than I ever did in elementary, junior high, and high school.

Xenobia Bailey, Funktional Design furniture prototypes, work in progress, 2020. Photo by Xenobia Bailey. Courtesy of the artist.

TW If you were getting D’s in high school, what made you want to go to college?

XB I had a passion to learn, and I wasn’t learning at all in school up to that point. We lived close to the University of Washington, and I used to watch students going on and off the campus. I wished I could go to the University of Washington. My parents could not afford to pay for college. My education was funded by the affirmative action program. I studied in the Black studies program, which was only made possible and was taught by the students who took over the university president’s office, which resulted in more minority students being accepted. They also demanded more ethnic studies programs be included in the university.

I majored in Black studies initially because I didn’t know what else to major in and our counselors advised us to. One of the many benefits of going to a university is that there are several colleges, and I followed my passions to the School of Music. My process for choosing a major was to sit in on a few classes that interested me, even if I wasn’t officially enrolled or auditing the class. One of the students in the dormitory was taking an ethnomusicology class studying the music, singing, dancing, and storytelling of Zimbabwe. She invited a few of us from our dorm floor to attend weekly performances. I sat in on a fabulous ethnomusicology course. I knew about anthropology and thought it could provide me with an opportunity to dive deeper into the cultures of the community that I’m from in Seattle.

From ethnomusicology, I discovered the study of non-Western material culture through the fieldwork of one of my professors. That really caught my eye. The performers were all making their costumes by hand from the indigenous materials growing around them.

When I transferred to Pratt, I decided to major in industrial design. I discovered there that design education for mass production stripped away all the life experiences from my community and what I had learned in ethnomusicology and Black studies. It required designing from a neutral point of view so that products could be fabricated on an assembly line. But I was fortunate to have instructors who saw what my challenges were, and they told me that I could design whatever I wanted as long as I could explain my concept and process.

I started doing more of the African American aesthetic after I proved how it could be a national American aesthetic and not only for the Black community. When I started in the industrial design program, the instructors told me the market wasn’t big enough to mass-produce African American material culture. I told them it’s just like Japanese ceramics or Italian rugs or French provincial furniture. People from all cultures buy these products. I realized I was working in an African American funkaesthetic, because that’s the aesthetic that I knew. I finally understood that I did not want to create an African American aesthetic for mass production on an assembly line; I wanted to design products that could be made by hand and fabricated in the underserved Black community to sustain the social and economic well-being of the community.

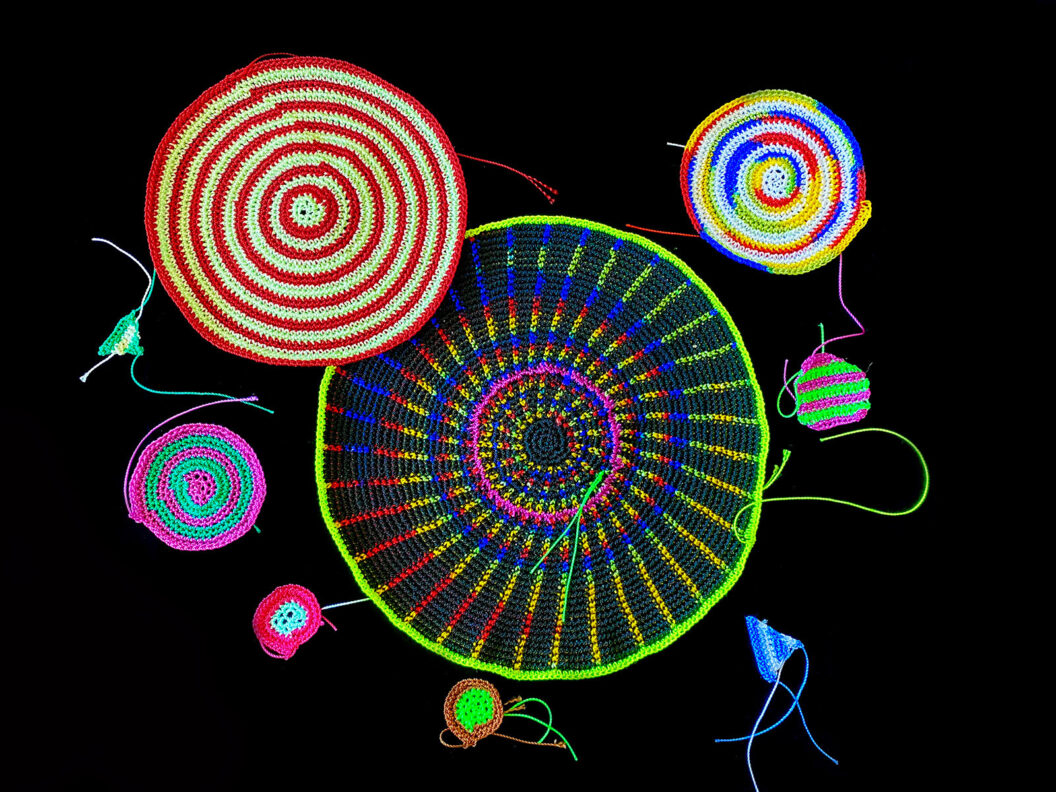

Xenobia Bailey, crocheted thread, color, and pattern studio exercise, work in progress, 2025. Photo by Xenobia Bailey. Courtesy of the artist.

TW Can you describe the African American funk aesthetic? Why funk and not jazz?

XB Funk is the core of everything I consume: food, material culture, literature. It comes from the African American community remixing culture, natural materials, and found objects with character. Jazz is a more sophisticated, cosmopolitan sound. Funk is gutbucket. It’s free-form like jazz, but it’s more medicinal and earthy. Funk is about grounded energy. I don’t think jazz has that grounded element to it. Jazz is cool, like Quincy Jones.

TW You and I have talked about George Clinton and Parliament-Funkadelic. Who else were you listening to as you were creating this design aesthetic? How did you make the connection between the sound and feeling of funk and the materials and visuals of what you were designing?

Xenobia Bailey, Cosmic-Roots, 2024, crocheted graphics printed on vinyl; and Moon Lounge, 2000, hand-crocheted four-ply cotton and acrylic yarn, 98 × 55 × 68 inches, in Poke in the Eye: Art of the West Coast Counterculture, Seattle Art Museum, 2024.

XB Music was not a major part of my formal visual studies, but the music and lyrics of George Clinton and the whole philosophy of Sun Ra gave insight into this funk aesthetic. There were many musicians in our neighborhood in Seattle whose practices and lives inspired me and who played a mix of funk, blues, and jazz. Most households had some kind of instrument, and the funk came more from the blue-collar, no-collar people. They wanted to get out and party hard and sweat after a hard day of working or trying to find a way to make a living. Jazz was mostly heard in clubs where everybody got dressed up and mellowed out.

TW Yeah. (laughter)

XB Funk can be made with any kind of instrument, or even everyday objects. You can make funk by beating a tin can. To me, it’s a more authentic sound. Jazz comes from instruments that can be used to makean African American sound. But funk creates a bridge between the continent of Africa and the field workers’ hollers in North America. It’s similar to gospel. You can call gospel music funk to a certain degree.

TW They feel similar to me sometimes. I grew up in church, and recently I have been listening to gospel as more of a secular person. There’s so much in it musically, and it does lead me straight to funk. Every time we talk, I go back and listen to funk for days because I’m trying to understand what you hear in it.

XB I think the core of my practice is the funk aesthetic, which comes from my study of the music produced in funk and its medicinal, groovy side, which is necessary for survival but not always respected within African American culture. Even though we have been at the core of the service industry, as domestic workers and custodians who nurture others, African American descendants of slaves haven’t gotten into healing ourselves through the medicinal quality of funk music and material culture. The medicine of funk has not been a traditional part of creating African American culture. The culture doesn’t prioritize our mental health and well-being; it prioritizes whatever gets attention for the right price. We should be trying to coexist with this planet and the cosmos, with our cultural practices and material culture, and we’re not doing it. We have more destruction than construction. A funk aesthetic requires us to be wholesome, to cocreate with everything around us. When I create, this funk aesthetic is in my head. I’m pulling from where I came from, what I dream, read, and hear. I solve design problems as I’m working through the process, as I’m answering questions. I see something that presents itself over time.

Support BOMB’s mission to deliver the artist’s voice.