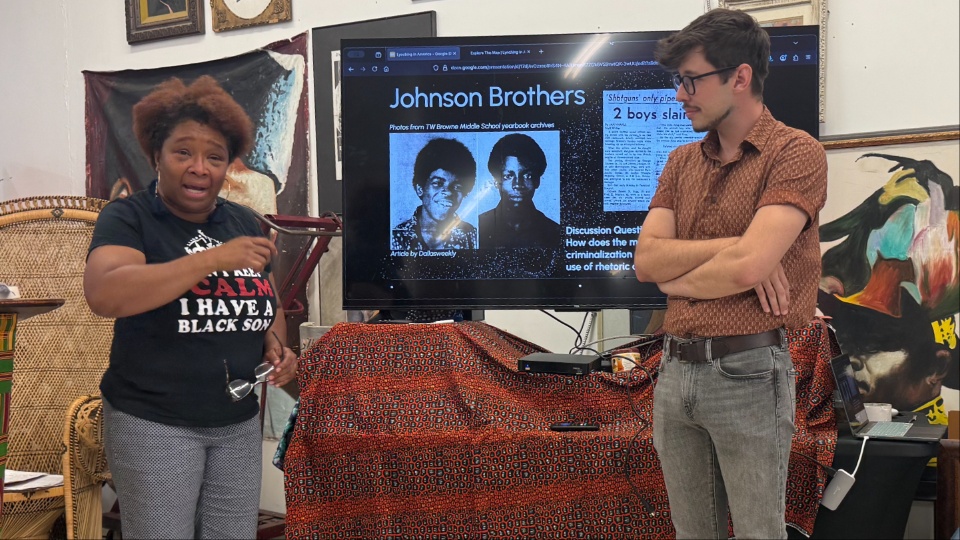

Historian and activist Olinka Green, left, and Dallas Nomad editor-in-chief Sam Judy. | People’s World

DALLAS—Activists in north Texas are getting an education about the history of lynchings in the United States, thanks to local historian Olinka Green, in conjunction with Dallas Nomad magazine. On Aug. 16, the Pan-African Connection Bookstore in Dallas was host to an educational presentation by Green and a panel of speakers focused on the history of lynchings of African Americans in the United States—both the vigilante type as well as the “legal” lynchings that happen via police brutality, the death penalty, prison, and environmental racism.

Green discussed how the lynch mobs carrying out the brutal murders of the 19th and 20th centuries were often organized and led by powerful figures in white communities, such as businessmen, politicians, and clergymen, and how the lynchings were treated as a twisted spectacle, with postcards celebrating the murders.

“The trains here in Dallas, Texas, if there was a lynching, you could get on that train free and go to any lynching in the state of Texas. There was money to be made, because you had to have a hotel, you had to have food, you had to have horses taken care of, it was a money-making industry,” Green said.

She discussed some of the most infamous historical incidents of lynchings, such as the murders of Laura Nelson and her 13-year-old son L.D. in Okemah, Okla., in 1911; Henry Smith in Paris, Texas, in 1893; and Allen Brooks in Dallas in 1910.

Green told of how entire communities were destroyed for attempting to resist lynchings, such as the Black neighborhood of Greenwood in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Rosewood, Fla. Green said there is a campaign underway in Dallas for a historical marker to be erected for Allen Brooks at the site of his lynching.

Sam Judy, editor-in-chief of Dallas Nomad magazine, gave a presentation about the racist murders of George and Johnny Johnson, African American children aged 13 and 14, who were killed by off-duty Dallas police officers Robert Ross and Fred E. Sexaur in 1974. The two boys were murdered for being in a white part of town after an argument with a white waitress, whom Officer Ross was dating at the time.

The police and local business communities responded to the murders by defaming the children, bringing up their juvenile records, to avoid charging the police officers with their deaths.

“We’re seeing this recurring narrative, that there’s an inherent lawlessness to Black life, and you also have to consider the fact this was also a very contentious time politically in Dallas,” Judy said. “It was the ’70s, this was when the Panthers were coming up, this was when the Brown Berets were also starting to work with the Panthers, this was a time when Black and brown populations in Dallas were especially under siege, in a way that is just as comparable post-9/11 to the way we targeted Muslim and Arab folk in the aftermath of that.”

Robert Ross, the main officer involved in the murders, would go on to get rich off the profits he made from the prison-industrial complex, running a company that operated private prisons, the Bobby Ross Group, before dying at age 71.

Green said that the demonization and othering of young Black men to justify their murders by the police and white supremacists is a recurring theme in history. She mentioned the killings of Mike Brown, Trayvon Martin, Emmet Till, and George Stinney.

Local Dallas activist Jarvas Wright gave a presentation on the prison-industrial complex and racist criminalization of the African American community, discussing how he was sent to prison for 13 years from age 18 to 31 for possession of crack cocaine. Racist sentencing laws made the criminal penalty for possession of crack cocaine, which was associated primarily with African Americans, 100 times more severe than powdered cocaine, which was more associated with white people.

Wright mentioned how many of his fellow prisoners couldn’t handle serving hard time and ended up taking their own lives. He got out of prison after he became eligible for resentencing after the racist Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 signed into law by Ronald Reagan was overturned during the first administration of President Barack Obama.

Wright went on to become an activist after the murder of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman in 2012, inspired by having a son of his own. “I had never participated in activism or anything like that, but the death of Trayvon Martin in 2012 stirred something up in me so tough, it made me think about my 15-year-old son, I had to do something.

“There was a rally in Downtown Dallas. I had to say something. That day an activist was born,” Wright said his decision to become politically active after spending so many years of his life in prison.

Green tied Wright’s presentation into the general exploration of lynching, referring to mass incarceration as “lynching” parts of the lives of young Black men.

Stu Becker, a Dallas labor activist, spoke about the role of the Communist Party USA in defending the “Scottsboro Boys,” a group of nine Black young men aged 13-18 who were falsely accused of the rape of two white women and sentenced to death in Alabama in 1931.

The Communist Party organized their legal defense via the International Labor Defense, a legal advocacy group started by the party to defend political prisoners. The Communist Party also published details of the case widely in the Daily Worker (predecessor of today’s People’s World), organized protests, and arranged speaking tours across the country and internationally for the defendants’ mothers to discuss the plight of their sons.

The Communist Party’s aggressive pursuit of justice eventually paid off when the executions were stayed, eventually being dismissed, saving most of their lives. Green added that the Communist Party’s international campaigning for the Scottsboro Boys, including in the Soviet Union, had a tremendous effect on pressuring the federal government of the United States to step in and dismiss the cases.

“Due to the Communist Party’s aggressive strategy of publicizing it [the plight of the Scottsboro Boys] and exposing the racist justice system of the South, they blew it up to be an international story,” Becker said.

“This made it so the world was watching the South. The trials went on for a long time, but eventually the party was able to save every one of the Scottsboro Boys’ lives, except for one who died in prison,” stated Becker.

After the presentations, the family of George and Johnny Johnson shared memories of their loved ones and details about their long fight for some semblance of justice. In a powerful conclusion, the event participants gathered around to pay respects to the family and give condolences.

We hope you appreciated this article. At People’s World, we believe news and information should be free and accessible to all, but we need your help. Our journalism is free of corporate influence and paywalls because we are totally reader-supported. Only you, our readers and supporters, make this possible. If you enjoy reading People’s World and the stories we bring you, please support our work by donating or becoming a monthly sustainer today. Thank you!