By STEVE PFARRER

For the Valley Advocate

Along with Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and Kwame Ture, Rosa Parks is one of the celebrated names of the civil rights movement: the Montgomery, Alabama woman who refused to move from her seat on a bus in 1955, sparking a historic bus boycott in that city that in turn helped jumpstart the push to end segregation across the Jim Crow South.

But outside of Parks, asks John Bollard, how many Americans today can name any Black activists besides Parks who protested segregation that persisted for decades on buses, trains, and planes, and before that on stagecoaches, steamboats, ferries and streetcars?

As Bollard, of Florence, notes, that list includes close to 100 Black Americans – including some with Valley connections – who fought for equality on public transportation as far back as the early 1830s.

In his newest book, “Protesting with Rosa Parks,” Bollard, a longtime writer, researcher and academic, has taken a deep plunge into period journalism, historical journals, court cases, letters and other sources to tease out stories of African Americans who risked physical assault, arrest, and substantial fines for defying efforts to confine them to segregated sections of transport.

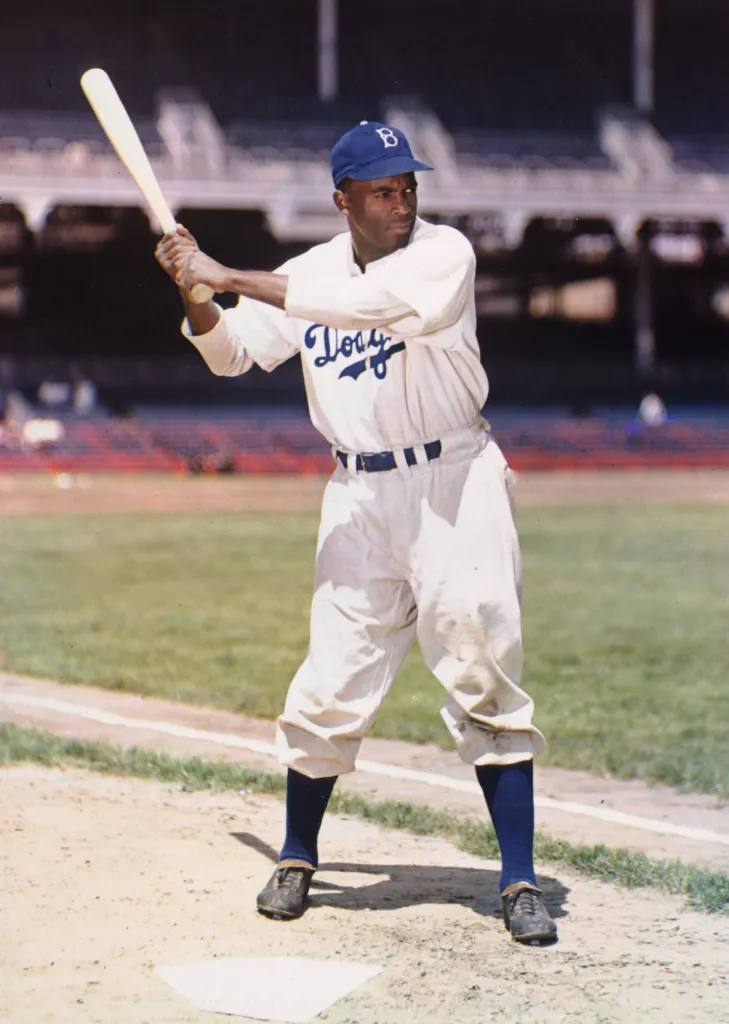

Some of those profiled are well known, like Jackie Robinson, who, before he broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball in 1947, faced a court martial in 1944 when, as a U.S. army lieutenant, he refused to give up his seat on a Texas bus (he was acquitted of all charges). Frederick Douglass, the most important Black leader of the 19th century, was thrown off a train in eastern Massachusetts in the early 1840s for refusing to move from a carriage with white passengers.

Jackie Robinson, who, before he broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball in 1947, faced a court martial in 1944 when, as a U.S. army lieutenant, he refused to give up his seat on a Texas bus (he was acquitted of all charges). / Wikicommons/Harry Warnecke

There are also accounts of lesser-known folks whose struggles had a dramatic effect on U.S. history, such as Isaac Woodard, a just-discharged U.S. Army sergeant who was beaten and blinded by a South Carolina police chief in 1946 following an argument with a white bus driver. (Not surprisingly, the policeman, Lynwood Shull, was acquitted by an all-white jury of any charges in the assault.)

But U.S. President Harry Truman was so horrified by the episode that he ordered the country’s armed forces to be desegregated in 1948. And Bollard notes that Woodard’s case led, in a more roundabout way, to the Supreme Court’s famous Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954 outlawing school segregation.

Yet many of the people he researched are largely unknown today, says Bollard, despite their actions representing important chapters in a longstanding history of protest before Rosa Parks.

“While I was researching this book, which involved some travel, I’d be in conversation with people and I’d ask them if they could name anyone other than Rosa Parks who had protested segregated seating,” he said during a recent phone call.

Only once, he says, did someone provide a name: Claudette Colvin, an Alabama teen arrested in Montgomery in 1955 (10 months before Rosa Parks) for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white passenger.

The young girl who asked him if he would be including Colvin’s story in his book “absolutely made my day,” Bollard said with a laugh.

Given the racial tension and inequality that persists in the U.S. today, he says, it’s important for this long history of protest not to be lost – perhaps especially now, when the Trump administration is actively promoting a revised historical narrative that minimizes negative aspects of the nation’s past such as slavery.

“I’ve had a lot of comments about the book from people who say ‘It’s very timely,’” said Bollard.

John Bollard, author of “Protesting with Rosa Parks,” in the Sojourner Truth Memorial Park. Staff Photo/Carol Lollis

Finding stories

Bollard, 82, has a deep background in historic Welsh poetry and literature, having written a number of books on those subjects and published several translations of medieval Welsh poetry. He has also taught English at a number of schools in the area, including the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and he once was a lexicographer for Merriam-Webster in Springfield.

But the inspiration for “Protesting with Rosa Parks” came from a stint in the early 2000s when he served as the executive managing editor of the African American National Biography Project, at the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute at Harvard University. As such, he says, he came across “a broad sweep” of stories of Black Americans, many of whom had faced incidents of racism and confrontation at some point over their seats on public transportation.

Bollard says he began work on the book about 14 years ago, pecking away at it for a time and initially thinking he might profile perhaps 20 people. “But I came across many others the more research I did,” he said.

And in the aftermath of the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police in May 2020, Bollard added, “I sort of woke up and said to myself, ‘You gotta get your ass in gear and get this book done.’”

It’s more than a little ironic and disturbing to read his accounts of Black passengers, such as Frederick Douglass, facing threats and violence for trying to sit in the same train carriages as whites in the early days of the railroad in Massachusetts, despite the state being a center of the abolition movement. Sometimes white passengers pitched in to throw Black passengers out of public transport.

Enforcement could be completely arbitrary, with some rail companies and train conductors rigidly separating Black and white riders and others leaving them be, even after laws were passed in the state in the late 1840s officially outlawing segregated seating.

Similar stories emerge in Pennsylvania, where an 1867 law was passed that disallowed the exclusion or expulsion of Black passengers from trains and streetcars. Yet shortly afterward, Bollard writes, a young Black schoolteacher, Caroline LeCount, signaled for a Philadelphia streetcar to stop, only to have the conductor pass her by and yell “We don’t allow (racial expletive) to ride!”

Undaunted, LeCount made a complaint to the Pennsylvania secretary of state, Bollard writes, which led to the conductor being arrested and fined $100 (about $2,200 today).

Among its stories, “Protesting with Rosa Parks” recounts how another seminal 19th century Black figure, Harriet Tubman, had her arm broken in 1865 while enroute to Auburn, New York, by a train conductor who refused to let her sit with white passengers, even though Tubman had a government pass for her work as a nurse tending wounded Union soldiers.

Harriet Tubman, the famous abolitionist and Underground Railroad “engineer” who helped scores of enslaved people to freedom in the mid 19th century. She suffered a broken arm when a white conductor and a number of men ejected her from a railroad car with white passengers in 1865, while enroute from Philadelphia to Auburn, New York. / Library of Congress

Sojourner Truth, the famed abolitionist who lived in Florence in the 1840s, also suffered an arm injury after being ejected from a streetcar in Washington, D.C., in 1865. And perhaps no one, says Bollard, fought harder for equality in transport seating than David Ruggles, the abolitionist, journalist, and bookseller who, before moving to Northampton in 1842, faced down a number of violent streetcar and stagecoach conductors and employees in and around New York City.

“He really created the model for protesting for your rights on public transportation,” said Bollard.

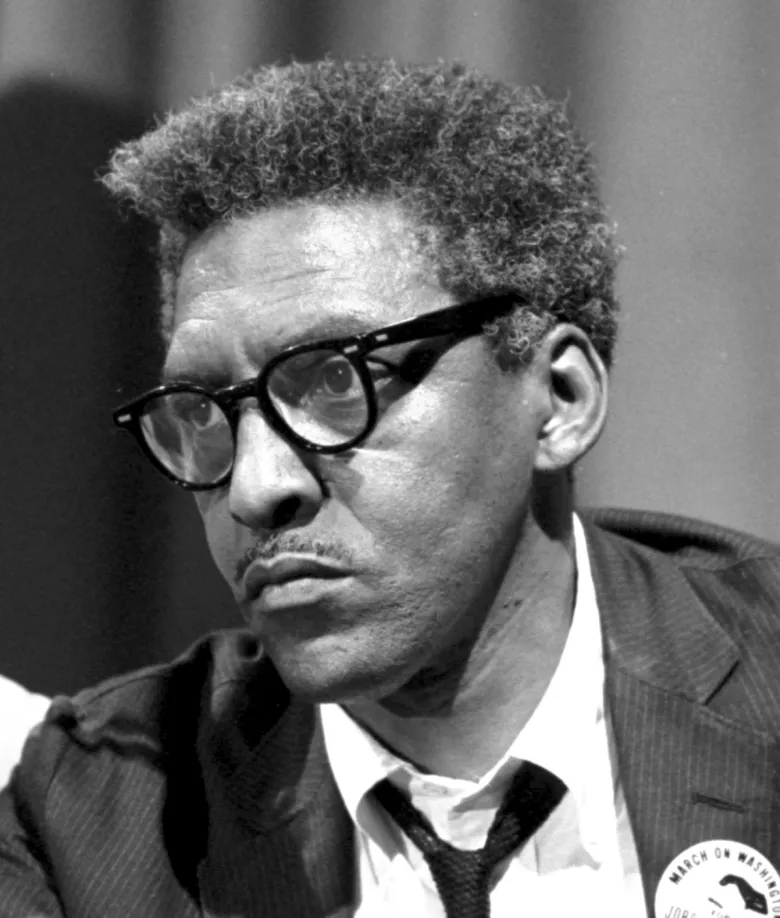

Civil rights activist Bayard Rustin who, in the late 1940s, began testing a 1946 Supreme Court decision banning racial discrimination on interstate travel by sitting in the white sections of buses in the South; he was repeatedly arrested as a consequence. / Library of Congress

Far from being repetitious, he adds, these individual accounts of Black Americans fighting inequality “never get boring – they’re never the same case. They’re all different, they’re all unique, they’re all inspiring.”

And as he notes in the book’s introduction, “Daily, mundane, malevolent acts lie at the heart of oppression … Experiencing something of that quotidian malice, even from a distance through the pages of a book, can bring us to a deeper understanding … (It) allows us to see history not as something that happened to ‘important’ people whom we learn about in school but rather as the combined experience of all of us.”

John Bollard will discuss “Protesting with Rosa Parks” Sept. 17 at 6:30 p.m. at the Bombyx Center for Arts and Equity in Florence. The event is free but advance registration is recommended at https://bombyx.live/. Bollard will also discuss his book Sept. 23 at 6 p.m. at the Tidepool Bookshop in Worcester.

Steve Pfarrer, a former arts writer for the Gazette, lives in Northampton.