On Sept 1, two patients — a threemonth-old baby and a 52-year-old woman — died within hours of each other at Kozhikode Govt Medical College. Doctors confirmed that both were being treated for primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), an infection caused by the free-living parasite Naegleria fowleri.By mid-Sept, the toll had risen to 19, with 69 suspected or confirmed cases across Kerala. Victims ranged from infants to middle-aged adults. The scale is extraordinary: globally, researchers have identified only 488 documented infections since 1962.

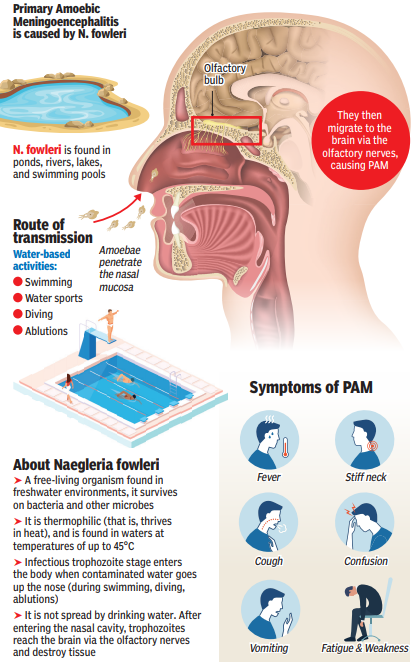

Rare And RuthlessPAM is one of the deadliest infections known to science. The parasite lives in warm, stagnant freshwater — ponds, lakes, unchlorinated swimming pools, poorly maintained tanks — and can infect people only when contaminated water is forced up the nose.From there, it travels along the olfactory nerve, burrows into the brain and begins dissolving tissue, unleashing catastrophic inflammation.Symptoms can begin in one to 12 days (typically 3-7 days): fever, headache, nausea and vomiting. Within days, they give way to stiff neck, confusion, seizures, hallucinations and coma.Across six decades, fewer than 20 survivors are documented globally, most with lasting neurological damage.The fatality rate is 97%.There is no vaccine or proven cure. Drugs such as Amphotericin B, Azoles, or Miltefosine are used in combination, sometimes with induced hypothermia, but success is rare. Crucially, PAM does not spread person to person and is not caused by drinking contaminated water; infection occurs via the noseWhy Kerala?Worldwide, PAM tends to appear as sporadic, one-off cases, usually tied to a single contaminated reservoir or swimming pool.Kerala’s outbreak is different. Cases have surfaced across Thiruvananthapuram, Kozhikode, Thrissur and Malappuram, with no single identified source.The state’s position as a public health bellwether makes the outbreak more unsettling. Kerala has often been the first to detect emerging threats: India’s first Nipah outbreak in 2018, its early Covid-19 cases in 2020 (detected in returning medical students from Wuhan), and Zika virus in 2021.The arrival of a rare, near-uniformly fatal amoeba on this list has alarmed both doctors and the public.“Eight people died in 15 days. What is the protocol? What are people supposed to do? Even a baby was infected — was that child in a swimming pool?” Opposition leader V D Satheesan asked in the state assembly this month.Protests have broken out in several districts, with residents demanding that wells and public taps be tested.Doctors caution that Kerala’s higher numbers also reflect better detection. “The symptoms — headache, fever and vomiting — are similar to bacterial and viral brain infections. If you don’t suspect amoeba, you’ll miss it completely,” said Dr Rajeev Jayadevan, convener of the Indian Medical Association’s research cell.How Kerala Is RespondingAmid mounting panic, Kerala has launched ‘Jalamanu Jeevan (Water is Life)’, a statewide chlorination drive covering wells, pools, etc.Schools have been told to disinfect storage units regularly, while panchayats and municipalities are checking public taps and wells.Hospitals, particularly in Kozhikode, Thrissur and Malappuram, are on high alert. Doctors have been instructed to treat any meningitis-like illness with a history of water exposure as potential PAM. Rapid-response teams have been sent to test community water sources, though no contaminated reservoir has been found yet.Drugs, including Miltefosine, have been stocked. But officials concede that treatment rarely saves lives. Survivors worldwide are exceptional, often treated with a cocktail of antifungals, antibiotics and cooling therapies. That is why prevention — keeping contaminated water out of the nose — remains the focus.Lessons For The WorldA 2025 review in the Journal of Infection and Public Health, which analysed 488 cases across 39 countries since the disease was first described, shows how there is little room for error — and what others can learn as climate change reshapes risk.The parasite is not the same everywhere: N. fowleri has multiple genetic strains; genotypes II and III predominate in Asia, North America and Europe.Clean water is the strongest defence: Free chlorine ≥ 2.0 mg/L in storage tanks/ pools can eliminate the amoeba; countries like Australia monitor disinfection as a routine public health practice.Surveillance changes the numbers: Strong labs and routine testing mean more detection (not necessarily more disease).Country tallies include India (26), Mexico (33), Czech Republic (17), New Zealand (9), Nigeria (4), Venezuela (7).Everyday habits can raise or reduce risk: In Pakistan, first cases were reported in Karachi in 2008; >140 cases have since been documented. Many were linked to nasal rinsing during ablution or showering, not swimming. A similar ablution-linked case has also been confirmed in the US.