Journalists Sense Turmoil in Their Industry Amid Continued Passion for Their Work

77% would choose their career all over again, though 57% are highly concerned about future restrictions on press freedom

From the economic upheaval of the digital age to the rise of political polarization and the COVID-19 pandemic, journalism in America has been in a state of turmoil for decades. While U.S. journalists recognize the many challenges facing their industry, they continue to express a high degree of satisfaction and fulfillment in their jobs, according to an extensive new Pew Research Center survey of nearly 12,000 working U.S.-based journalists.

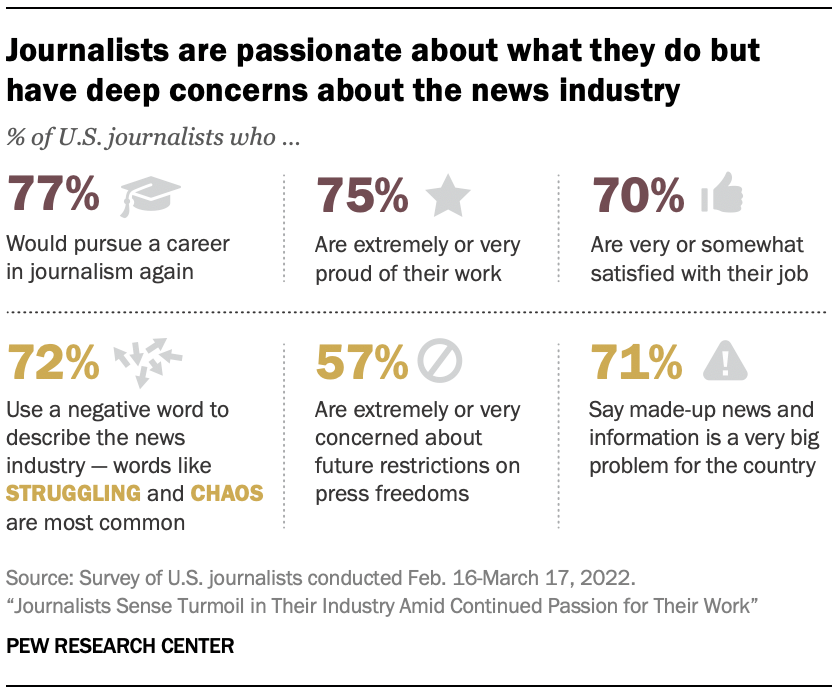

Seven-in-ten journalists surveyed say they are “very” or “somewhat” satisfied with their job, and an identical share say they often feel excited about their work. Even larger majorities say they are either “extremely” or “very” proud of their work – and that if they had to do it all over again, they would still pursue a career in the news industry. About half of journalists say their job has a positive impact on their emotional well-being, higher than the 34% who say it is bad for their emotional well-being.

At the same time, however, journalists recognize serious challenges in the news media more broadly. Indeed, when asked to describe their industry in a single word, nearly three-quarters of journalists surveyed (72%) use a word with negative connotations, with the most common responses being words that relate to “struggling” and “chaos.” Other, far less common negative words include “biased” and “partisan,” as well as “difficult” and “stressful.” (See Chapter 1 for more detailed figures and the methodology for more details about the question asked.)

The survey of 11,889 U.S. journalists, conducted Feb. 16-March 17, 2022, identified several specific areas of concern for journalists, including the future of press freedom, widespread misinformation, political polarization and the impact of social media.

More than half of journalists surveyed (57%) say they are “extremely” or “very” concerned about the prospect of press restrictions being imposed in the United States. And about seven-in-ten journalists (71%) say made-up news and information is a very big problem for the country, higher than the 50% of U.S. adults who say the same. At the same time, four-in-ten journalists say that news organizations are generally doing a bad job managing or correcting misinformation.

A large majority of journalists say they come across misinformation at least sometimes when they are working on a story, and while most say they are confident in their ability to recognize it, about a quarter of reporting journalists (26%) say they have unknowingly reported on a story that was later found to contain false information.

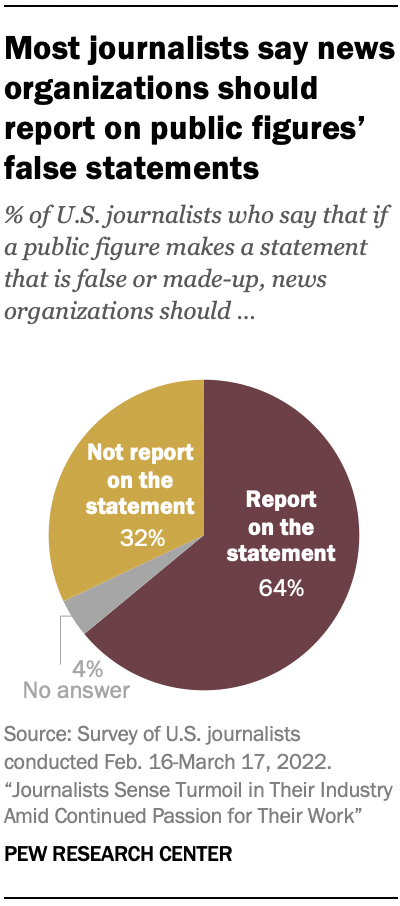

How to report on false statements has become a vexing question for journalists amid a turbulent political climate. The survey asked journalists what they think is the best approach to coverage when a public figure makes a false statement. By two-to-one, journalists are more likely to say the best approach is to “report on the statement because it is important for the public to know about” (64%) rather than to “not report on the statement because it gives attention to the falsehoods and the public figure” (32%).

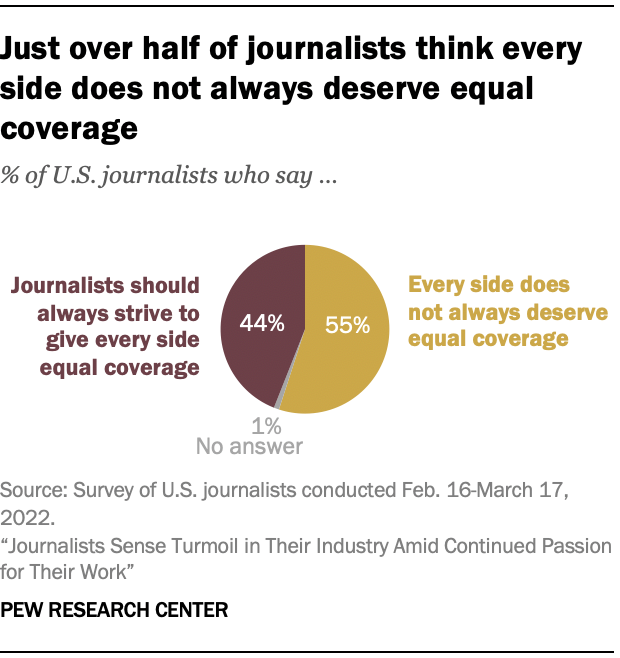

Still, there is no consensus that opposing views always warrant equal coverage. What historically may have been considered a standard norm of journalism (and even a requirement for broadcast stations in their election coverage) seems, in today’s political environment, to be facing a reevaluation as heated debate ensues around the issue of “bothsidesism” – whether news outlets should be committed to always giving equal attention to all sides of an issue.

A little over half of journalists surveyed (55%) say that in reporting the news, every side does not always deserve equal coverage, greater than the share who say journalists should always strive to give every side equal coverage (44%).

On the other hand, journalists express wide support for another long-standing norm of journalism: keeping their own views out of their reporting. Roughly eight-in-ten journalists surveyed (82%) say journalists should do this, although there is far less consensus over whether journalists meet this standard. Just over half (55%) think journalists are largely able to keep their views out of their reporting, while 43% say journalists are often unable to.

Some of journalists’ views – such as whether every side deserves equal coverage – are connected to the ideological composition of their audiences. Journalists were asked about the political leanings of the audience at the organization where they work (or the main one they work for if they work for more than one), and roughly half say that their audience leans predominantly to the left (32%) or right (20%). An additional third say their organization has a more politically mixed audience, while 13% are unsure.

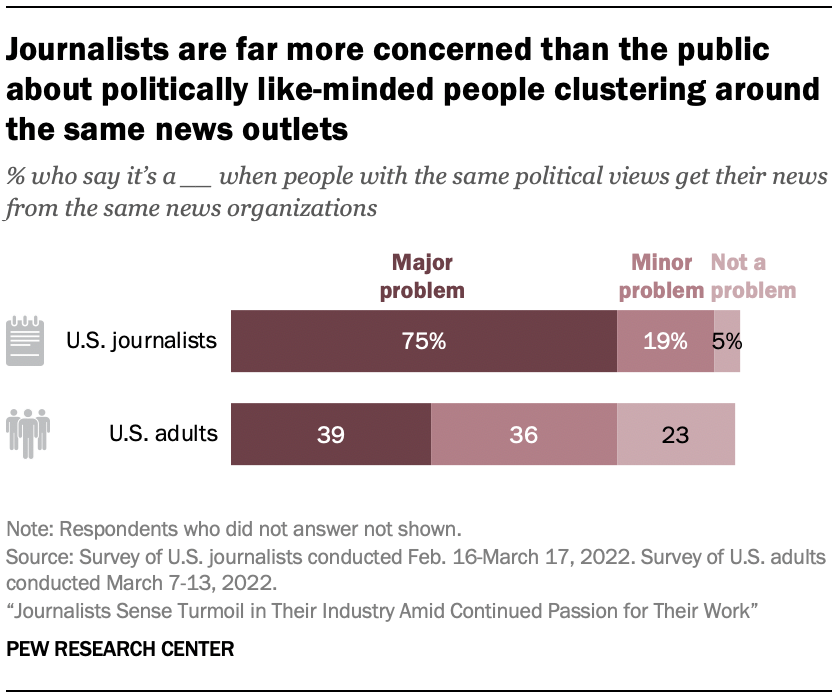

Even as they recognize audience leanings, journalists express deep concerns over political sorting in news consumption habits, with three-quarters of those surveyed saying it is a major problem when people with the same political views get their news from the same news organizations. The American public, however, appears much less worried: Roughly four-in-ten U.S. adults (39%) say this a major problem. To be able to make comparisons between journalists’ views and those of the public on certain key issues, the Center conducted two separate surveys around the same time as the journalist survey, posing some of the same questions to roughly 10,000 U.S. adults who are part of the Center’s American Trends Panel. (Read more about those two surveys in the methodology section.)

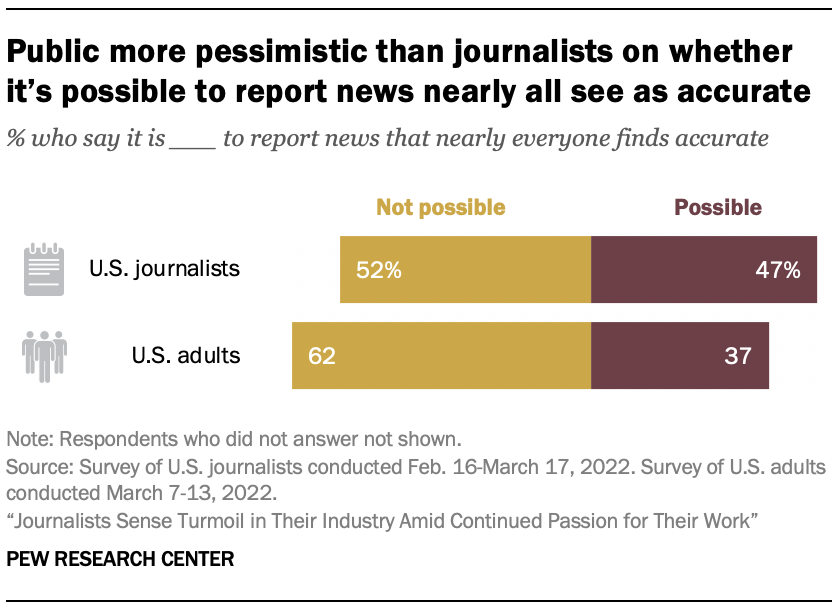

Maintaining widespread journalistic credibility in a polarized climate can seem like an impossible task – and many journalists seem to recognize that. While three-quarters of journalists say that journalists largely agree on the basic facts of the news – even if they report on them in different ways – about half of journalists surveyed (52%) say it is not possible to report news that “nearly everyone finds accurate.” An even greater share of the U.S. public overall (62%) says it is not possible to report news that is universally accepted as accurate.

Journalists and the public far apart on their assessment of today’s news industry

The survey’s results show that journalists recognize that the public views them and their work with deep skepticism. When asked what one word they think the public would use to describe the news industry these days, journalists overwhelmingly give negative responses, with many predicting that the public would describe the news media as “inaccurate,” “untrustworthy,” “biased” or “partisan.” (Read the methodology for more detail.)

Moreover, just 14% of journalists surveyed say they think the U.S. public has a great deal or fair amount of trust in the information it gets from news organizations these days. Most believe that Americans as a whole have some trust (44%) or little to no trust (42%).

When a similar question was posed to the general public, 29% of U.S. adults say they have at least a fair amount of trust in the information they get from news outlets, while 27% say they have some trust and 44% have little to none.

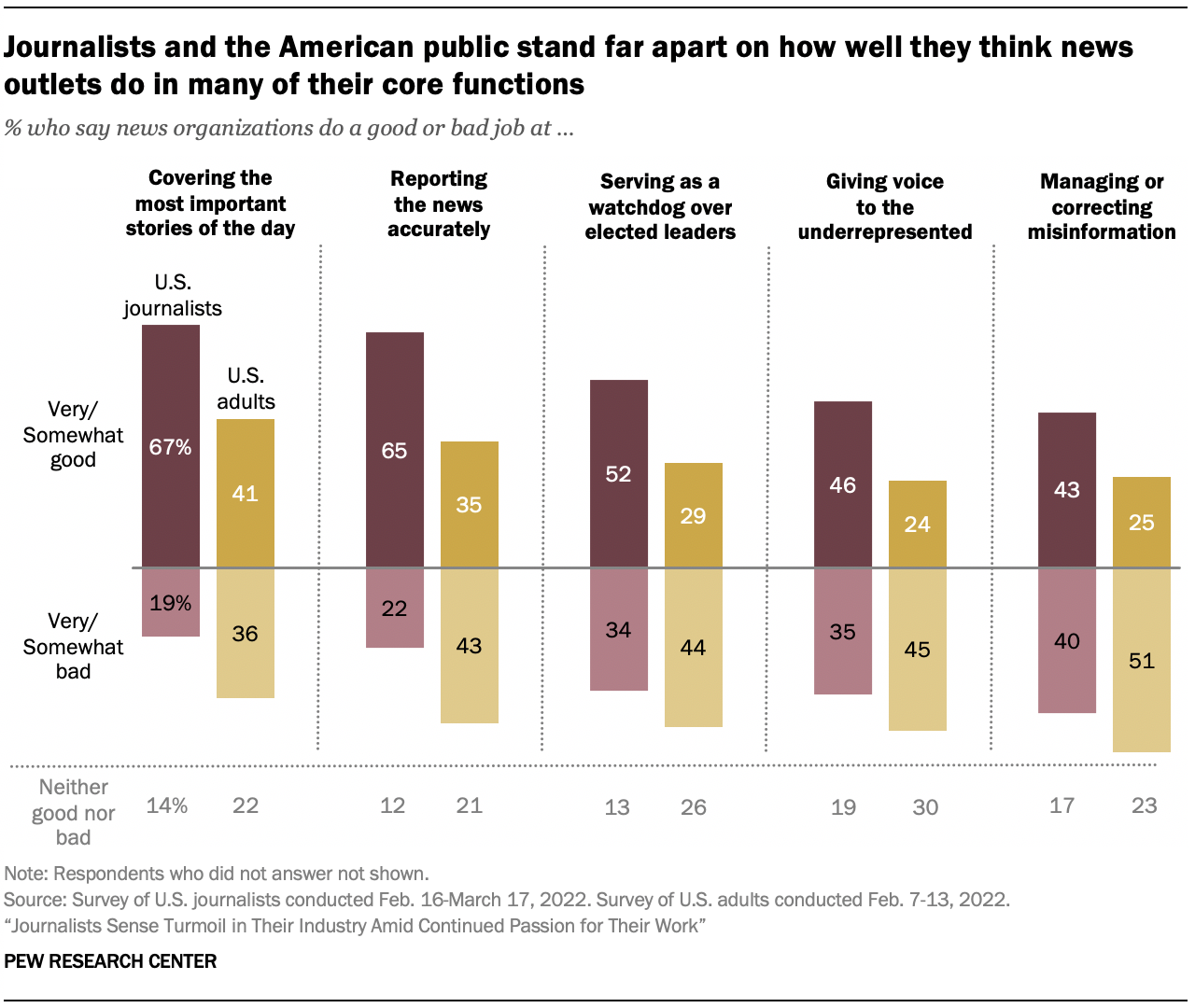

This disconnect between journalists and the public also comes through when each group is asked about the job news organizations are doing with five core functions of journalism: covering the most important stories of the day, reporting the news accurately, serving as a watchdog over elected leaders, giving voice to the underrepresented, and managing or correcting misinformation.

In all five areas, journalists give far more positive assessments than the general public of the work news organizations are doing. And on four of the five items, Americans on the whole are significantly more likely to say the news media is doing a bad job than a good job. For example, while 65% of journalists say news organizations do a very or somewhat good job reporting the news accurately, 35% of the public agrees, while 43% of U.S. adults say journalists do a bad job of this.

Similarly, while nearly half of journalists (46%) say they feel extremely or very connected with their audiences, only about a quarter of the public (26%) feels that connection with their main news organizations.

Journalists see social media as both a blessing and a curse

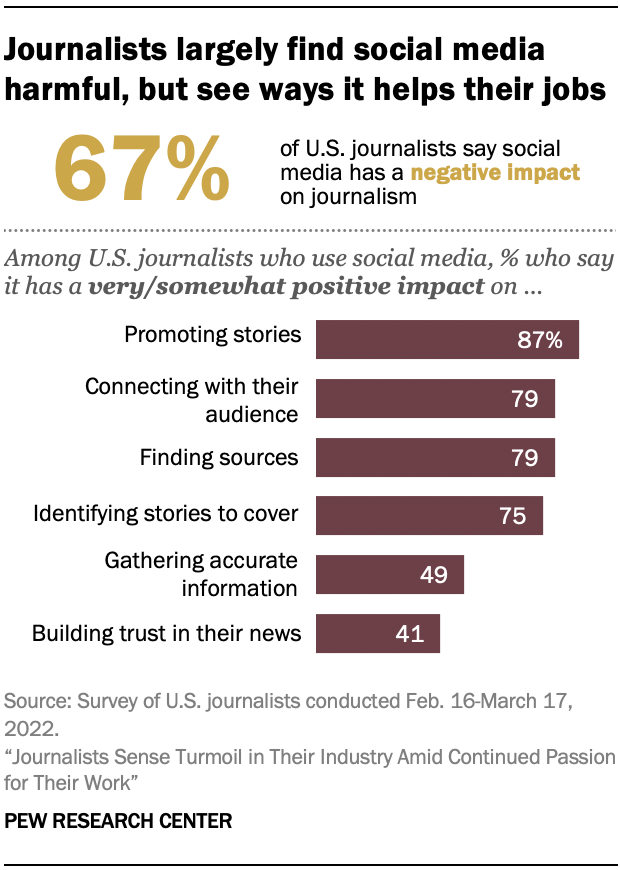

These days, many journalists connect with audiences through social media, and they see this as a double-edged sword. On the one hand, 94% of journalists surveyed report using social media in their work to some degree, and these journalists see a number of ways that social media helps them do their jobs. For example, among journalists who use social media for their work, 87% say it has a very or somewhat positive impact on promoting news stories, and 79% say it helps them connect with their audience and find sources for their news stories.

At the same time, however, two-thirds of all journalists surveyed (67%) say social media has a very or somewhat negative impact on the state of journalism as a whole. Just 18% say social media has a positive impact on the news industry, while 14% say it has neither a positive nor negative impact.

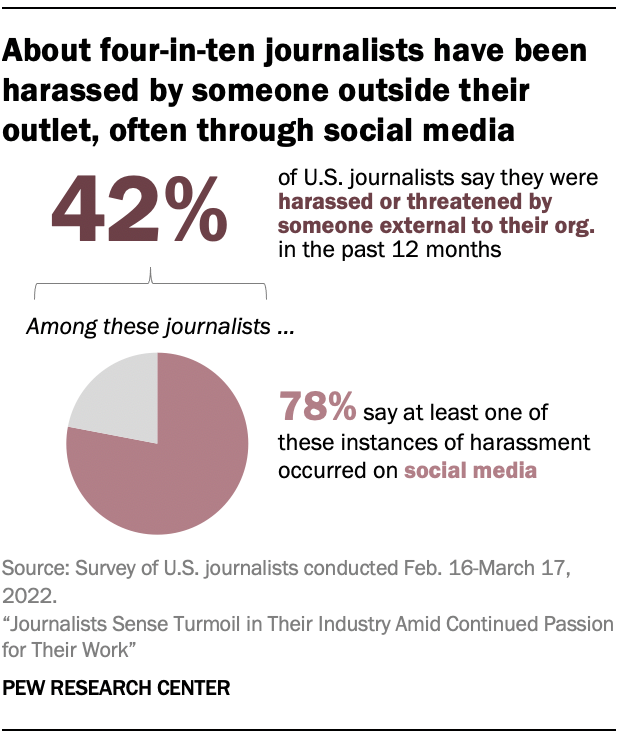

Additionally, roughly four-in-ten journalists (42%) say they have experienced job-related harassment or threats by someone outside their own organization in the past year, and within this group, a large majority (78%) say that harassment came through social media at least once. That means that one-third of all journalists surveyed report being harassed on social media in the last 12 months.

Journalists offer mixed views about diversity and inclusion in the newsroom

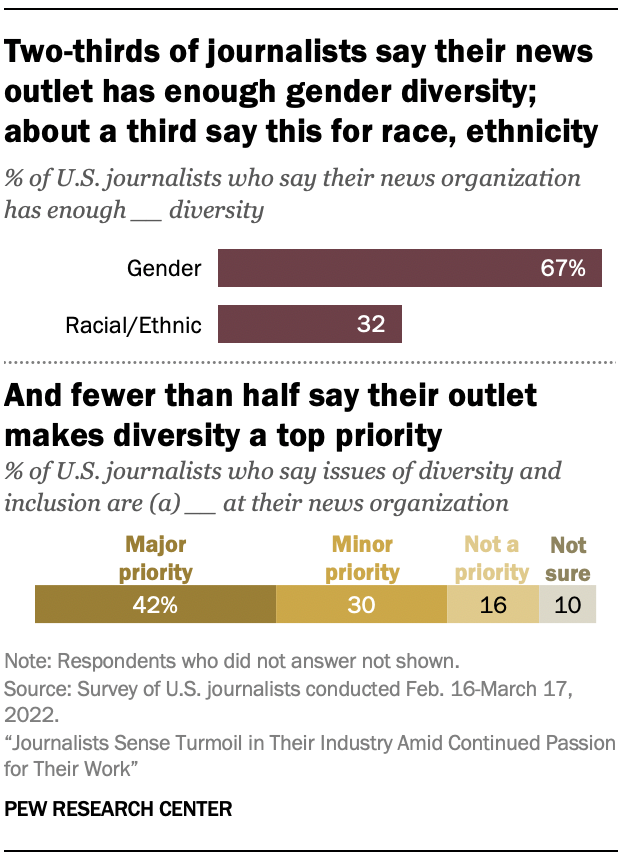

As issues of diversity and inclusion in the workspace gain heightened attention around the country, journalists offer mixed views of how their organizations are doing at diversifying staff. Although two-thirds (67%) say their organization has achieved sufficient gender diversity, about half as many – 32% – say it has reached sufficient racial and ethnic diversity. And fewer than half of respondents (42%) characterize addressing issues around diversity and inclusion as a major priority for their newsroom.

Roughly two-thirds of journalists say their organization generally treats everyone fairly regardless of age, gender, or race and ethnicity. But these figures are not quite as high among certain groups. For example, Black, Hispanic and Asian journalists are less likely than White journalists to say that their organization treats everyone fairly based on race and ethnicity. Read Chapter 6 for more details. (The appendix provides a detailed demographic profile of the journalists who completed the survey.)

Younger journalists give lowest grades on newsroom diversity, older journalists more worried about the future of press freedom

In a number of areas, there is a large amount of agreement across different groups of journalists. Still, some differences do emerge – particularly by age.

The youngest journalists (ages 18 to 29) are least likely to say their organization has enough diversity in the newsroom in a number of areas. For instance, nearly seven-in-ten (68%) say there is not enough racial and ethnic diversity, compared with 37% of journalists ages 65 and older who say the same. Younger journalists also engage with this issue more: About half of journalists under 50 say they discuss their organization’s diversity with colleagues at least several times a month, far higher than the 30% of those 65 and older who say this.

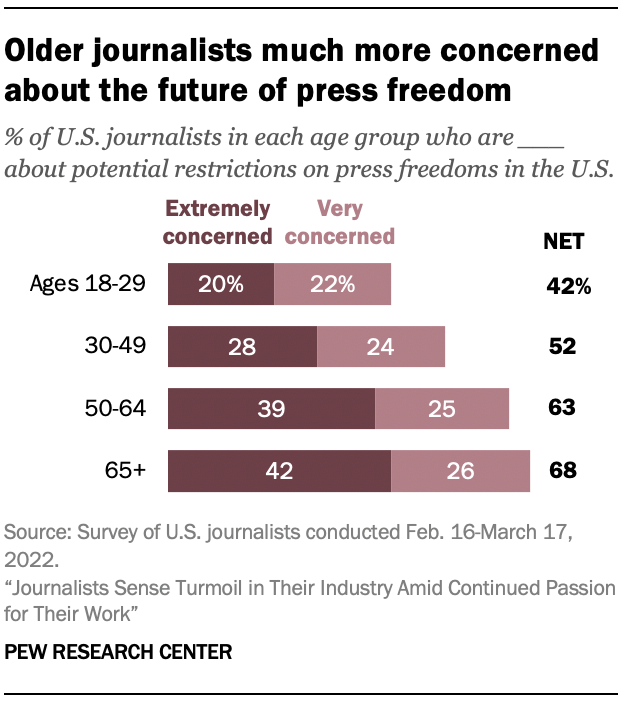

The oldest group of journalists, meanwhile, tend to feel more fulfilled by their job. Three-quarters of journalists 65 and older say their job has a very or somewhat positive impact on their emotional well-being, substantially higher than the 29% of journalists under 30 who say the same. Older journalists, meanwhile, are more worried about the future of press freedom – 68% say they are extremely or very concerned about possible restrictions on press freedom in the country, compared with 42% of those ages 18 to 29. (Read Chapter 7 for more details.)

Other key findings from the survey include:

- The survey sought to gauge the financial standing of journalists and the economics of the organizations they work for. The findings could be read with optimism or concern – depending on one’s vantage point. About four-in-ten journalists surveyed (41%) say they received a salary increase in the past year. The greatest portion – 50% – say their salary has stayed the same, while far fewer (7%) experienced a pay cut. Looking at news organizations more broadly, journalists are somewhat more likely to say their news organization has been expanding (30%) in the past year than to say it’s been cutting back (22%), with absence of change again being most common (46%). All in all, many journalists – 42% – say they are at least somewhat concerned about their job security, though far fewer express the highest level of concern.

- Despite concerns about the spread of misinformation and reporters inserting their own views into stories, about three-quarters of journalists (74%) say that people should be allowed to practice journalism without needing a license, while one-quarter say people should be required to have a license should in order to practice journalism.

- The vast majority of journalists surveyed say that at least some of the stories they have worked on in the past year had to do with the COVID-19 pandemic. But perhaps even more striking, six-in-ten say that the pandemic has brought either a great deal (26%) or a fair amount (34%) of permanent change to news reporting at their organization.

- Journalists’ opinions also sometimes differ based on the platform of their organization – particularly journalists who work in television. Compared with those in print, audio or online journalism, journalists who work for an organization that originated on TV seem the least happy with their job. About one-third (34%) say the news industry has a very or somewhat positive impact on their emotional well-being, considerably lower than the 54% of those who work online, 52% who work in print and 48% who work in radio or podcasting who say the same. And TV journalists are much more likely to say they were harassed by someone outside their organization in the past year (58%).